Report: The Drivers of Increasing College Price Aren't What You Think

By Allie Bidwell, NASFAA Senior Reporter

There are generally a handful of camps of thought when it comes to explaining why college has become more expensive over time: states are not investing enough in their public higher education systems, increases in financial aid have driven increases in tuition, and administrative bloat and the amenities race have added unnecessary expenses. But according to a new report from the Midwestern Higher Education Compact (MHEC), none of those reasons is entirely correct.

Over the last several years, much of the discussion around higher education has focused on the steady increase in tuition since the end of World War II, but more specifically since the 1980s. But oftentimes the conversation misses the mark in focusing on the increase in the sticker price, or list-price, tuition rather than the actual amount the average student pays. In a new report, MHEC analyzes the forces behind the increase in list-price tuition, as well as the drivers pushing up the cost of providing a college education.

The explanation is complicated, and two-fold.

List-price tuition has increased for a number of reasons, including changes in the cost of providing a year of higher education, changes in subsidies such as state appropriations, and increases in the use of institutional tuition discounts, the report said.

Within the issue of the rising cost of delivering a college education, the authors also dive into the misconceptions associated with the increase, pushing back against the idea that administrative "bloat" and amenity competitions have led to cost increases.

In order to understand why the cost of college—that is, the cost of "producing a year of college education"—has increased faster than the overall rate of inflation, it's important to look at higher education as part of the rest of the economy, the authors wrote. Accounts that fixate solely on increases in tuition have too narrow of a focus, the report said.

"In some cases, they highlight phenomena driving costs in higher education without realizing these same forces are also driving costs in the rest of the economy," the report said. "Finding something that pushes up costs in higher education is only half of the job."

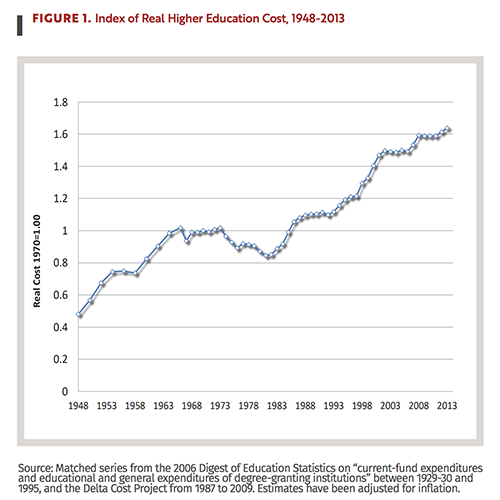

Additionally, looking at college cost over a greater span of time reveals that college cost rose even more rapidly between the end of World War II and the late 1960s than it has since the early 1980s. What's more, the authors noted that between those two periods of increases, college cost was stable or declining for more than a decade. That distinction may rule out some other popular narratives that attribute increasing cost to inefficiency.

"Unless universities became significantly more efficient in the 1970s, dysfunction arguments have trouble explaining an extended period of declining real cost," the report said.

One reason college cost has grown at a pace higher than the overall rate of inflation is that, much like other personal service industries (such as doctors, dentists, or lawyers), higher education is plagued by "cost disease." Other industries can increase their productivity (increasing their "output" relative to their "input") to make a profit by implementing new technology, for example. But for higher education to increase productivity, the report said, institutions would have to do things like cram more students per professor into courses and compromise quality.

"In most personal services, the quality of the service is directly related to the time spent with the service provider," the report said. "If quality is important to customers, personal service providers will not seek productivity increases that lower quality. In the absence of technological improvements that allow a university to shed labor without compromising quality, productivity growth in higher education will lag productivity growth in the rest of the economy."

Still, this "cost disease" is only one factor contributing to college affordability. Deeper-reaching issues like income inequality and decreases in state appropriations provide more of a driving force behind "the contemporary affordability crisis."

Higher education is also unique in that it requires a larger proportion of highly-educated workers than some other industries, and that it is expected to maintain a sort of "standard of care" or quality of the educational programs delivered. While some other industries will only adopt changes in operations or new technologies if they increase revenues or lower operation costs, institutions may make those changes "even if the older ways are less expensive."

"Any institution that fails to keep current may be committing educational 'malpractice,'" the report said.

Those three issues—cost disease, paying for highly-educated workers, and maintaining a standard of quality—all drive the overall increases in the cost of delivering one year of a college education. That increase in cost is just one of several factors behind the increase in sticker price tuition, along with decreases in state appropriations and changes to other subsidies, and tuition discounting.

Overall, though, the authors note that the increase in sticker-price tuition has outpaced the growth rates for net tuition—what students actually pay on average.

"Commentaries focusing on list prices miss the story," they wrote. "Explosive growth in college cost is not the main reason tuition is rising rapidly. If state appropriations had not fallen, real net tuition would have shown very modest growth in the public sector as it did in the private sector. And if colleges had not increased their use of tuition discounting, list-price growth would also have been more modest as well."

They argued that issues with access and affordability are related more to changes in the national distribution of income than "soaring" costs of delivering a college education and that policy solutions should focus on developing effective federal-state partnerships, reforming the Pell Grant program (by indexing the maximum award to inflation and preserving year-round Pell), and improving communication on the difference between sticker price and net tuition for students.

"Useful policy remedies would put more resources into the hands of middle- and lower-income families and more resources into student support and educational expenditures at schools that enroll large numbers of these students," the report said.

(Photo Credit: Midwestern Higher Education Compact)

Publication Date: 8/15/2018

You must be logged in to comment on this page.